This frustration stems partly from the difficulty caused by post-modern existence: nothing now remains under the sun, especially in a world in which the actors are so mundanely engaged with one another.

Here, Atwood focuses the reader on the writer’s creative task, which she appropriates as being somehow threatened by the inevitability of its end. In “Happy Endings,” the plot becomes a central character despite that is routinely dismissive throughout as something susceptible to contrivance, though not through its means of construction, but only by its end. The reader recognizes the formalist's approach in Atwood’s story a kind of re-direction of their attention from the climactic tension that engages the reader with a plot’s ultimate end and the act of creating that which allows for this end an end that may captivate or devastate, but which is certain to have been made possible only through the work performed by the writer in the course of leading to it. As such, Atwood focuses the reader on the creative impetus of the writer, both liberating the writer from self-applied pressure and also vindicating him or her by calling the reader’s attention to the difficulty of their task. Indeed, for Atwood, “True connoisseurs, however, are known to favor the stretch in between, since it's the hardest to do anything with” (Atwood 3).

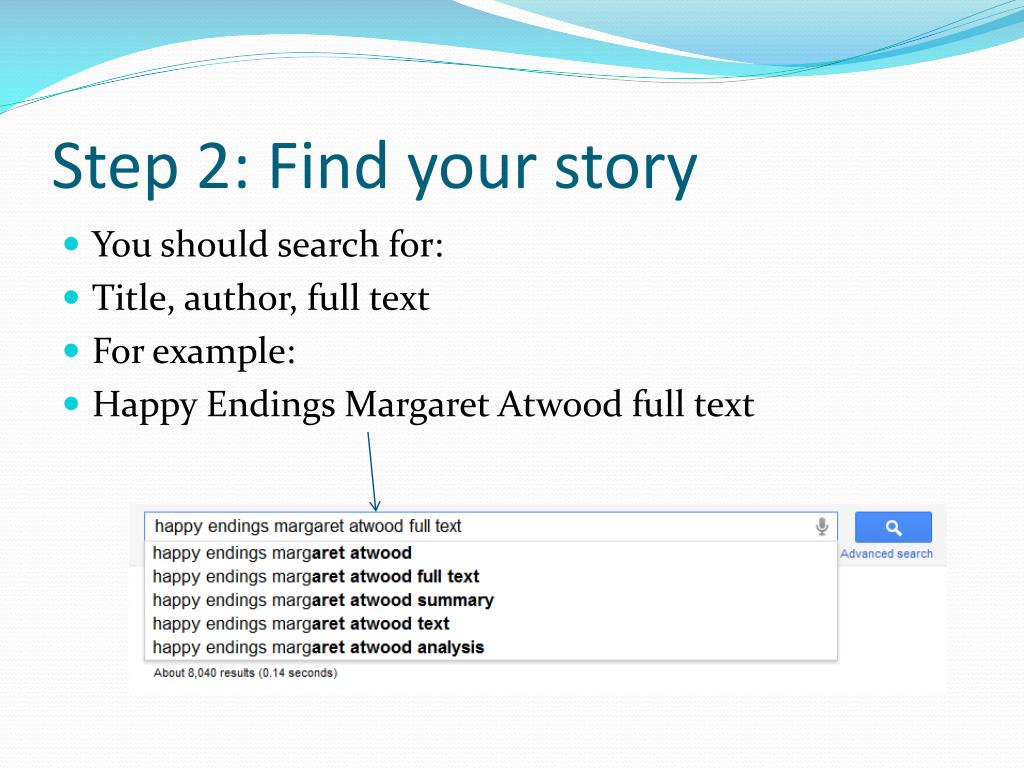

#Happy endings margaret atwood work cited free

There is a kind of liberating quality inherent in this sentiment, as Atwood seems to seek to free herself from the non-creative process of adjusting plot to suit reader comfort. Don't be deluded by any other endings, they're all fake, either deliberately fake, with malicious intent to deceive, or just motivated by excessive optimism if not by downright sentimentality” (Atwood 3).

Her “counterespionage” plotline is admittedly “fake,” but this does not mean that it will or should be any more maligned than less contrived plotlines: “You'll have to face it, the endings are the same however you slice it. In the course of making her point, Atwood distinguishes between plots designed to make life easier on the writer and those that are genuinely crafted.

#Happy endings margaret atwood work cited full

The story thus emerges as a kind of guided tour through the creative process relevant to fictional work, as Atwood exposes the reader to the full but limited range of human tropes and mores upon which the writer may draw. In this sense, Atwood seems to suggest that a subtly refined simplicity in her conception of the construction of fiction: that all plots end in some form of death, just as do all lives in the real, which renders all fiction not merely microcosmic illustrations of daily human interactions, but microcosmic demonstrations of the human life cycle, for better or for worse. Much like the storyline in her other renowned work, The Handmaids Tale, in order for this to occur, characters must be actively engaged in life, as opposed to death. In this sense, Atwood speaks not merely to the potentiality of death as a given plot’s driving force, but also the manner in which death depends upon the plot’s constituents-the players-for purposes of progressing to its logical conclusion. What first emerges from Atwood’s formative work of meta-fiction is that each plotline ends in death, though each death is provoked by some human act as against the deceased party. As such, instead of railing against the difficulties of derivative writing styles or a post-modern dearth of originality, Atwood uses the story as an opportunity to speak to the power of the plotline to dominate the creative process, but also its capacity for frustrating it as a result of the expectations of the reader, in addition to the manner in which the reader engages with the real. In reality, Atwood provides through the story a glimpse into the frustrations entailed in the literary creative process, but from an unusual angle in that she engages the reader in her frustrations, and for good reason: for Atwood, the reader is partly to blame for these frustrations. If it were not so central to one of the more pressing questions relating to the creation of fictional literature, “Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood might be considering something of a pessimist’s tale.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)